George Floyd

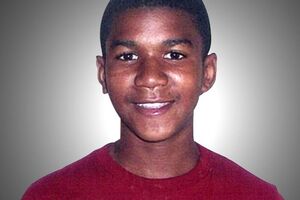

George Floyd  Travon Martin

Travon Martin The Zimmerman prosecutors mishandled the same three issues the Chauvin prosecutors employed to secure a conviction. First, the Zimmerman prosecutors did not negate the emotional distancing tactics used by the defense. Throughout the trial, the defense attorneys painted a narrative in which Zimmerman acted to protect his residential community from burglars, at least one of whom was black. Because the prosecutors did not strongly argue against this narrative, it allowed the defense to taint Trayvon as a criminal and thug. Second, the prosecutors failed to address critical elements of the case: why would Trayvon attack Zimmerman, and how did Trayvon know Zimmerman carried a gun on his back. Trayvon talked on his cell phone to a girl who testified that he feared Zimmerman when he first started following Trayvon. It did not make sense for Trayvon to attack someone from whom he was trying to hide. The prosecutor’s presentation obscured the testimony that Trayvon feared Zimmerman. More importantly, Zimmerman wore his gun on his back. If, as he testified, Trayvon was on top of him, Trayvon would have been unable to see or grab Zimmerman’s gun. The prosecutors failed to highlight this inconsistency in Zimmerman’s story. Third, the prosecutors did not push for a U.S. African-American jury member on the six-person jury. The only African American was a Puerto Rican who deferred to two white women jurors. These women had family members who were lawyers and advised them about the evidence presented. They used their greater fluency of the evidence to overcome the African American’s predisposition to convict Zimmerman.

There were other problems with how the prosecutors presented their case. Experienced trial lawyers, such as Lisa Bloom, Suspicion Nation, and Honey Howard Rothschild’s A Million Prosecutor Mistakes, have written books on how the prosecutors mishandled the case. They point out that the initial investigation of the shooting was too limited and may have missed essential facts such as whether the photos purporting to show wounds to Zimmerman’s head were valid. Also, the prosecution may have undercut their case by agreeing with the defense to exclude reference to Florida’s “stand your ground” law. That law may have allowed the prosecutors to argue that Trayvon had every right to defend himself from Zimmerman. Finally, the prosecutors did not fully explain the elements that were needed to convict Zimmerman of manslaughter. If they had, the jury might have convicted Zimmerman of manslaughter even if they could not agree on the second-degree murder charge.

Because prosecutors work closely with the police, many have been reluctant to bring charges against police officers. Activists have therefore focused on having police officers charged. But just as prosecutors may not want to charge officers, they may also do less than a stellar job in prosecuting them. The prosecutors in the Chauvin case have provided a partial template of how convict officers charged using excessive force. Although most observers celebrated the conviction of Chauvin, they recognized that convicting one or four officers did not address the systemic failures evident in policing.

Nonetheless, some prosecutors may use the methods used in the Chauvin trial to convict other police officers of unwarranted violence. Of course, the motives and abilities of prosecutors will always affect the outcome. Now, at least, activists will have a standard by which to measure prosecutors. And when they find prosecutors are lacking, activists will have a transparent basis for complaint.